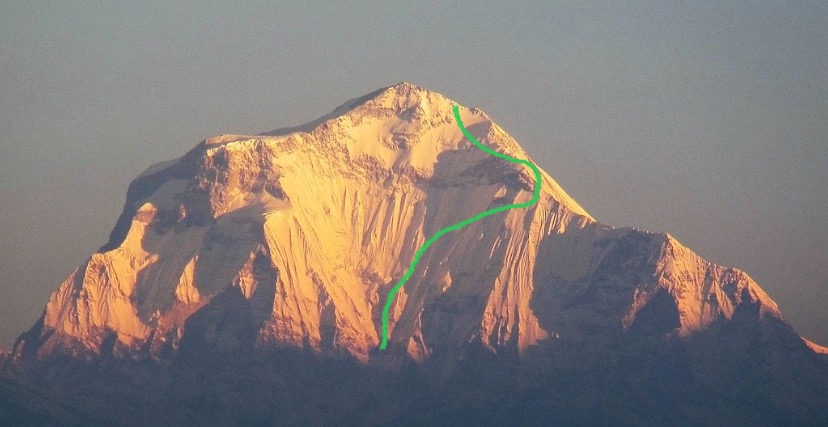

The 4,100m South Face of Dhaulagiri I has stymied great climbers since 1977. It is one of the last big undone challenges on an 8,000m peak.

Until the end of 2023, 417 expeditions have attempted Dhaulagiri I. Among these, only five targeted the South Face of the White Mountain. The immense, beautiful wall, with tricky concave sections, seracs, and avalanches, has a few partially opened routes. But no one has completed the wall to the summit.

The South Face of Dhaulagiri I. Photo: HITED Nepal

Team Messner, 1977

In 1977, two parties went to Dhaulagiri I. One arrived in the spring and the other in the autumn. The spring team was the first-ever expedition to focus on the South Face. It included Italian Reinhold Messner (leader), Austrian Peter Habeler, German Otto Wiedemann, and American Michael M. Covington. The party also had five sherpas, a film crew, and several kitchen staff. Except for Pemba Tsering, the names of the sherpas were not recorded in the official climbing reports.

The team arrived at the 4,000m base camp on April 2 via the previously unexplored Thula Khola. Several days later, the climbers scouted their line and concluded that their planned route (left of center on the main face) was too risky. Instead, according to Covington’s report for the American Alpine Journal, they decided to place another camp beneath the south pillar on the extreme left edge of the face.

The first attempt on Dhaulagiri I’s South Face, 1977. Photo: Raphael Duprat/Wikipedia

Slow progress

However, they did not progress far on the south pillar because of route difficulties beneath unstable hanging glaciers. That spring had brought plenty of snow too, and avalanches threatened constantly.

On April 19, Messner and Habeler, climbing without supplementary oxygen, reached 6,150m before halting.

“Virtually every possibility on the enormous 4,115m face proved unjustifiably dangerous,” Covington concluded in his report. “Any feasible route was threatened by some kind of objective danger, either on the route or the access to it.”

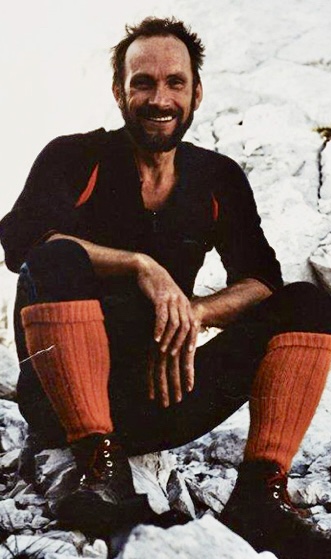

Stane Belak. Photo: Goat.cz

A bold Slovenian attempt in 1981

Four years later, on Sept. 23, 1981, the Slovenian Himalaya Expedition arrived at base camp beneath the South Face. Under the leadership of Stane Belak, the team included Cene Bercic, Janez Sabolek, Rok Kolar, Emil Tratnik, and Joze Zupan. The expedition had no sherpas and did not use bottled oxygen.

The party’s original plan was to ascend the left part of the face, but big avalanches and serac falls made that route impossible.

After several days of bad weather during which they studied the route, they realized it was impossible to acclimatize on the face itself. Instead, they headed to a nearby hill to acclimatize to 6,400m. Afterward, the party chose the right side of the south wall for their ascent.

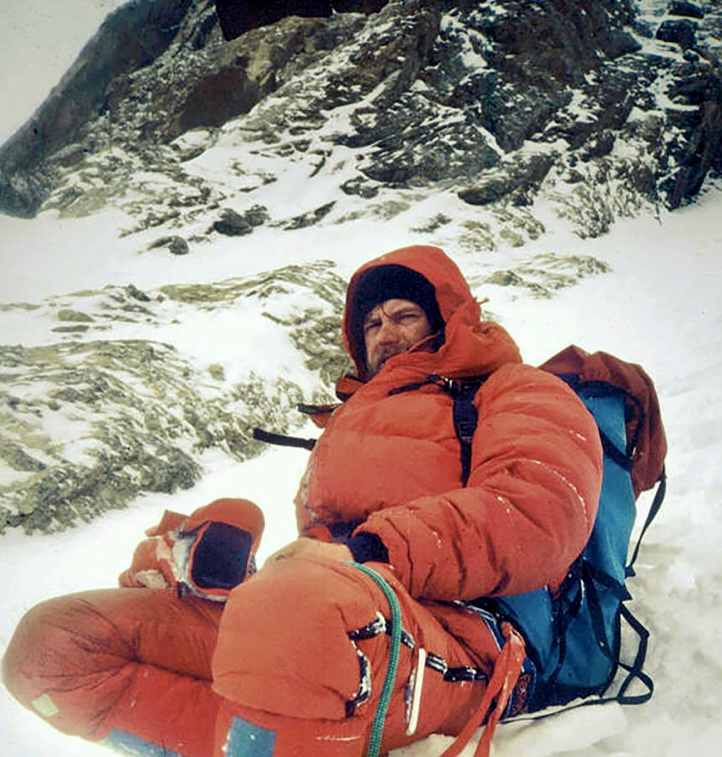

Tratnik, left, and Bercic on the South Face of Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Goat.cz

Belak, Bercic, and Tratnik started from base camp on Oct. 16. The following day, they waited seven hours at 5,550m because of heavy rockfall. Once the rockfall stopped, they progressed to 5,700m.

On Oct. 17, the climbers ascended a 50º icefield and the third rock band of the route. Progressing on such dangerous terrain was mind-blowing, but they did not turn around and bivouacked at 6,100m.

On Oct. 18, they made their second bivy at 6,400m. A third bivy on Oct. 19 at 6,935m followed. The next day, they traversed toward the Japanese route and joined the southeast ridge at a rock band. At 7,300m, they found some fixed ropes.

One of the climbers at 7,400m in 1981. Photo: Goat.cz

From this point, their progress slowed considerably. On Oct. 21-22, they gained only 250 vertical meters. The next day, they gained the right-hand edge of the huge snow slopes below the summit, at 7,803m. It seemed they had solved the most difficult part of the route, but then the weather turned. On Oct. 24, they reached their highest point on the southeast ridge at 7,950m. There, they left some gear.

A complicated descent

The climbers started down via the northeast ridge but had to bivouac during the descent. The Oct. 25 bivy was particularly rough, a night without food or shelter in terrible weather. They continued down in harsh conditions the next day, reaching a crevasse on the northeast col at 5,950m.

They finally reached the bottom of the rock and ice face at 4,700m in the dark, trudging through fresh snow. From there, they could see distant villages and continued toward Tak Khola.

But the suffering wasn’t quite over. On Oct. 28, the climbers spent 12 hours traversing the dangerous glacier. They bivouacked in the moraine.

Vinko Bercic on the northeast ridge of Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Goat.cz

They went without food for the final six days, before eventually meeting some Belgian trekkers on Oct. 29, who gave them some food. They reached a village a day later, according to Franci Savenc’s report for the American Alpine Journal.

The Slovenians had started to get frostbite during their descent. “Tratnik no frostbite, Stane [Belak] a little frostbite, Vinko [Bercic] frostbite on all hands and feet,” Elisabeth Hawley noted in The Himalayan Database.

The 1981 Slovenian route. Photo: Raphael Duprat/Wikipedia

Although the team celebrated their climb as the first ascent of the South Face, they did not climb the face completely. Even so, this was a brave attempt, without sherpas above base camp and without supplementary oxygen. They climbed in strong winds and terrible weather, making five bivys without food. They described the South Face as very steep and icy.

The South Face of Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Summitpost

The 1986 Polish attempt

A Polish party led by Eugeniusz Chobrak established a base camp at 3,800m on Thula Khola’s east moraine on Sept. 16, 1986. The 16-member team included two Canadians. They began the South Face close to the Messner party’s starting point. Chobrak’s expedition used no sherpas above base camp and also did not use bottled oxygen.

On Sept. 21, the party set Camp 1 on the lower part of the prominent buttress just to the left of the center of the face. This first part of the buttress was a 1,200m high rock wall. On its upper part, at 5,800m, they placed Camp 2 on Oct. 4.

According to Chobrak’s report, the crumbly rock presented continuous difficulty. “Part of it was so friable that a bolt hole could be made with a few blows,” he recalled.

The terrain became even trickier above this section because the route continued up a 60º to 70º ice rib, with passages up to 85º.

On Oct. 26, the climbers set up Camp 4 at 7,100m. They fixed 3,200m of ropes, although rock avalanches cut the ropes several times.

Maciej Berbeka on K2 in 1988. Photo: Cultura de Montania

No way up

On Oct. 30, Maciej Berbeka and Mikolai Czyzewski established Camp 5 at 7,500m. But strong winds tore their tent apart during the night.

The next morning, Berbeka ascended alone to the southwest ridge, joining the 1978 Japanese route. From there, the terrain seemed a bit easier to the summit, but with the weather deteriorating and their tent shredded, they gave up and descended to base camp. Their highest point was 7,550m on Nov. 1.

The Polish route of 1986. Photo source: Raphael Duprat/Wikipedia

Solo attempts

In 1987, Japanese climber Hiroshi Aota tried the South Face solo. But in bad avalanche conditions, he abandoned his autumn attempt at 4,300m before even starting the face. “Winter would be a better time to try this face,” Aota concluded.

The last attempt on the South Face was 25 years ago, in the autumn of 1999, by Slovenian Tomaz Humar. It was one of the greatest solo climbs in Himalayan history. Humar climbed alone in alpine style, without sherpas or supplementary oxygen. A film crew came to document his ascent.

Base camp during Humar’s 1999 expedition. Photo: Tomaz Humar

On Oct. 25, Humar set foot on Dhaulagiri I’s South Face at about 5 pm. He climbed until 2 am, reaching 4,600m where he bivouacked. From this first bivy, he continued to the top of a rock wall to scout the route. He returned to the same bivouac to sleep.

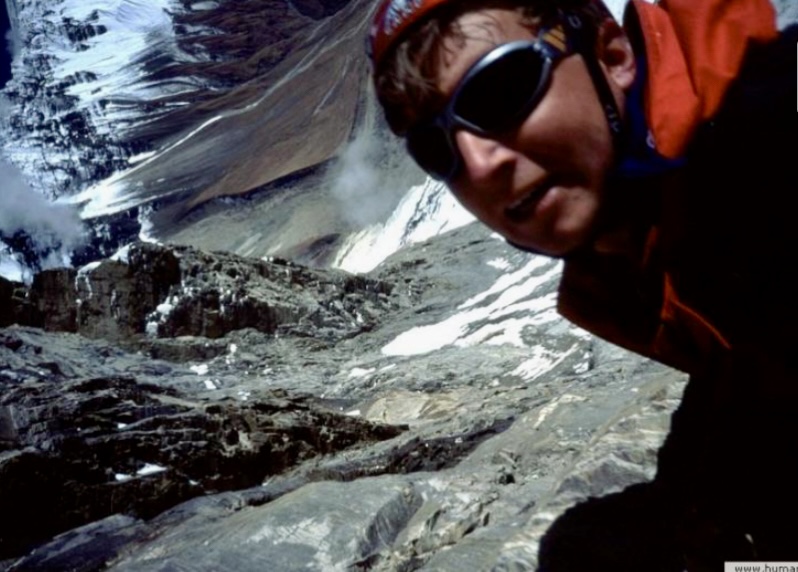

Tomaz Humar in 1999. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Hit by falling rock

On Oct. 27, Humar rock climbed up to a snow slope. He made a second bivy at 4 am a day later, at around 5,700m. While he was resting, a large falling rock hit his leg. Humar was fortunate not to be seriously injured.

He left his bivy at 2 pm that day and reached the lower end of a serac by 2 am. He spent the night at 6,300m. According to his report for Elisabeth Hawley, it took him nearly three hours to gain 20 vertical meters on one section of snow and ice.

Tomaz Humar on Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Tomaz Humar

The next afternoon, Humar reached the top of the serac. He made his fourth bivouac there, at 6,800m. A day later, he reached 7,100m and spent his fifth night on the wall. Next, he started to traverse toward the southeast (Japanese) ridge.

In the afternoon of Oct. 30, he confronted a major rock band across the face at about 7,300m. Humar realized it would take him two or three days to continue up a direct line over the band. Instead, he decided to traverse around to the east.

Tomaz Humar looks down on Dhaulagiri I in 1999. Photo: Tomaz Humar

To the ridge

On Oct. 31, he completed the 1,000m traverse and climbed a smaller rock barrier to the southeast ridge at 7,300m. He spent his sixth night there.

The next day, to move more quickly, he decided to leave his tent, rope, almost all pitons, slings, and his two ice screws at his bivy spot. At 8 am, he started up the southeast ridge before moving back onto the South Face. At 7,700m, he bivouacked for the seventh time.

On Nov. 2, Humar continued to the southeast ridge at 7,900m. He briefly crossed the East Face in very strong winds to the northeast ridge. However, conditions were so bad that he knew if he wanted to live, he should abort and descend.

Tomaz Humar’s impressive Mobitel Route on the South Face of Dhaulagiri I in 1999. Photo: Raphael Duprat/Wikipedia

Humar finds Ginette Harrison’s body

On his way down the northeast ridge, Humar found a tent at 7,300m left for him by an American climber. He spent a night there before continuing down. He also found the body of Ginette Harrison of the UK, who had died in an avalanche just a couple of weeks previously.

On Nov. 3, he reached Camp 1 at 5,600m via the standard northeast ridge route. There, he waited for a helicopter to evacuate him. It came the next day and flew Humar back to Pokhara.

Humar named his line the Mobitel Route (VI 5.10d AO M7+).

After the climb, Reinhold Messner stated that he considered the South Face finally done. According to Messner, topping out on the summit was secondary to finishing the face.

Tomaz Humar drytools at 7,600m on Dhaulagiri I. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Humar’s Nirvana

In an interesting interview with Antonella Cicogna, published in the American Alpine Journal in 2000, Humar reflected on the climb.

“The South Face has everything. It’s the highest face in Nepal, damned overhanging and steep. It’s the face par excellence, more than 4,000m of climbing, the dream of the super strong Strauf [Stane Belak]. The idea was also born thanks to him. I chose it for this reason. It’s my Nirvana.”

Humar’s climb was among the boldest of his career, along with Bobaye. The renowned Slovenian climber died on Langtang Lirung in 2009.

The challenge of climbing the South Face of Dhaulagiri I entirely to the summit remains. It’s a tantalizing problem for future climbers ready for this level of commitment. The question is, who will dare?

The four routes opened on the South Face of Dhaulagiri I. None ended on the summit. Humar’s line is in yellow. Photo: Tomaz Humar